Squash Coaching

September 24, 2014 § Leave a comment

Thomas Lowish, UC Berkeley Squash coach, has graciously shared with me the three resources he uses the most to structure the team practice. I am looking forward to adapt some of these materials for the Wake Forest Squash Team.

(1) http://www.squashsite.co.uk/squash_drills.htm (Not available anymore. But can see it on Wayback here)

(2) http://www.squash-training.com/squash-resource.html (Not available anymore. But can see it on Wayback here)

Graphical Representation

April 11, 2014 § Leave a comment

Visual communication predates writing…

Caves of Chauvet, Paleolithic Era Circa 35,000 b.C.

But together with writing it implies a degree of abstraction that both helps communicate and also think the world around us. On the Mayan Codex of Dresden we can see for example, side by side, columns of phonetic scripture and numeric representations in base five, which helps understand and signify the number « O » common in Mesoamerican carvings in the first century b.C, 1300 years before Arab mathematicians introduced it to Europe, in the 12c.

Mayan writings circa 8c, reproduced in the Codex Dresden circa 11c a.D.

Graphic representations and texts complement each other and serve a double purpose of thinking and communicating. Pythagoras theorem by Leonardo or Euclides’ Elements circa 300 b.C. offer a good example of the later, while the graphical representation of Orbis Terrarum in Medieval manuscripts illustrates the later.

Leonardo’s illustration of Pythagoras theorem

Oliver Byrne’s edition of Euclides’ Elements, London 1847

Orbis Tertius & Mare Oceanum

The idea that graphic representation needs to accurately depict the relative magnitudes of what it is representing is necessary for deriving conclusions and using them as a thinking devices, but not for telling a story as is the case of the schematic representation of Orbis Tertius.

William Playfair’s 1821 engraved charts of historically declining purchasing power in the UK, Florence Nightingale’s rose graphs showing poor living conditions of military barracks in 1855, and especially Charles Minard’s graphic representation of Napoleon’s Russian campaign of 1812 started a turning point in visual representation of statistical data.

Edward Tufte’s The visual display of quantitative information (1983), Envisioning information (1990) and Beautiful evidence (2006) are considered the start of its associated scholarly inquiry. The chapter entitled « Chartjunk » in Beautiful evidence is often used as a basis for workshops on «Power Point communication best practices » for example the one that Ray Lyons addressed to medical research professionals in Baltimore, MD on 2010: “Best Practices in Graphical Data Presentation.” Stephen Few wrote an interesting review of the state of the “Chartjunk debate” in 2011 for business professionals.

Often quoted sources are Howard Wainer Visual Revelations (1997), Graphic Discovery (2005) and Picturing the Uncertain World (2009); Dona Wong the WSJ Guide to Information Graphics (2010) and Stephen Few Now You See It (2009), Show me the Numbers (2012) and Information Dashboard Design (2013). In terms of a textbook with a systematic step by step overview of the discipline, my favorite is Ricardo Mazza’s Introduction to Information Visualization (2009). The discipline has grown significantly in recent times with research focusing on data mining and visual thinking of big data.

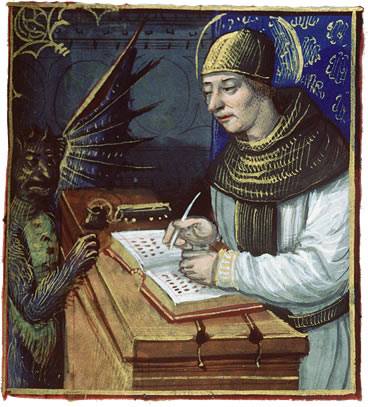

Titillius demonio de las erratas

March 27, 2014 § Leave a comment

Working in groups

February 26, 2014 § Leave a comment

Interesting questions are never answered by one person alone. Not that they once were, and then now they are not, but the romantic pretension of one author-one text has been loosing traction in many fields for a long time. So what is the app for teamwork?

I see there are actually tons.

Google Apps, Skydrive, iCloud and the new Mailbox/Dropbox interface all let you work collaboratively. Adobe Cloud and all major suits are offering cloud integration too. You have the usual suspects in desktop applications: Conceptdraw Project, Merlin, OmniPlan, xPlan all of which have a considerable learning curve and demand a very significant amount of time to input data if you want them to be useful. Some interesting programs such as ProjectX and Mori no longer exist.

There are many cloud-based project management apps that seem to be more flexible. A simple Internet search shows some of the top contenders for small projects used to be Basecamp, Jira, Asana and Trello but that people are fleeing away from Basecamp in large numbers and Jira needs a degree in Jira before being useful. Asana is oriented towards CEOs and Trello towards team members. Mark Suster wrote an interesting comparison of them here. Flow, Convo, Podio, Mavenlink, ProWorkFlow, NetSuite, Wrike, Insightly, Liquidplanner, Freshbooks, WorkZone, OpenProject… the list seems endless. Streak adds Customer Relationship Management (CRM) to your Google email, Boomerang adds functionality to your Google calendar, etc. Some of those apps seem to be suited for business, others for architects, I haven’t seen one clearly directed to research groups, although I have been invited to collaborate on some research using Google Apps and Adobe Cloud.

An interesting fact is that you can find 2014 reviews of the “10 best Project Management software for Mac” that do not cite any of these apps!

What app would be better to manage a small research group / think tank? The question is still open…

The last day of class

November 20, 2013 § Leave a comment

Just as the first day sets the tone for the rest of the course, the last day of class creates the student’s last impression of the class.

The last day can serve as a reflection and round-up of the course that makes the connection between individual session to students who are often too busy preparing for next day, to take a step back and figure out how all ties-up together. It can include a review of the syllabus and what was accomplished as a class stressing contents but also class engagement and student’s motivations to learn and use the material. It can stress how students can use that material in life, in other courses, their major or their college experience in general. A concept map can be a good exercise to give a visual representation of the course and how all ties in together.

The last day of class can also include a review for the final exam, which could nicely connect with the syllabus review and concept map. Students can be asked to write questions they think should be part of the final exam, some of which may actually be used. One question I include in midterms and finals is what important concept of the section was not covered by the exam. Students need to explain through a structured argument what the concept is, what it means and why they think it is relevant.

The last day of class can also include student evaluations, which the two prior exercises would help get more focused and with a better perspective of the whole course. Do not bring cookies, or candies that day if you don’t want to read that students perceive you are trying to influence their comments.

The last day of class can also help students imagine future learning. Students can be asked to write anonymous letters advising future students on how to succeed in the course, giving them tips of does and don’ts. Students can be asked to share their most significant experience in the course and what they are going to remember the most of it. They can be asked to fill the blanks in “Before this course I_____________ and now I_____.

The last day of class should be relaxed, include time for Q&A, give students an overview connecting all elements of the class and reminding them of its objectives, while making their knowledge visible. It can present sample exam questions and tell them how to prepare but above all it is a time for the instructor to praise students for their efforts and achievements and give them a chance to say goodby.

Intercultural Communication: an introduction

November 18, 2013 § Leave a comment

Edward Hall’s book The Silent Language (1959) is often cited as the starting point of the field of Intercultural Communication in the United States. During WWII and at the beginning of the Cold War between 1946 and 1956, the U.S. Foreign Service Institute and the Department of State hired some of the best linguists and anthropologists to train members of the Foreign Service. Rather than traditional broad topics taught to college students, the task was to focus on small elements of culture, and on the role of non-verbal communication in social interaction. It has been argued that this prompted Hall’s book and the institutionalization of the discipline (Leeds-Hurwitz, 2014).

There are today a vast number of intercultural communication institutions, journals, book collections and conferences. A simple Google search shows the following amongst others: the International Communication Association, the International Academy for Intercultural Research, the International Association for Intercultural Communication Studies, or the Intercultural Communication Institute; the Journal of Intercultural Communication, the Journal of International Communication Research, the International Journal of Intercultural Relations, and Cultus: the Journal of intercultural mediation and communication.

The introductory course on Intercultural Communication for advanced undergraduates and graduates in U.S. Universities has also been subject to a relatively rich academic inquiry. A number of scholarly articles have dissected how it has been taught, with which goals, contents and methods. Some of these relfections are: Gudykunst, Ting-Toomey & Wiseman (1991), Milhouse (1997), Kalfadelis (2005) and some recent book reviews of textbooks, anthologies, readers and handbooks.

A multidimensional approach

Reviewing such a vast material can be daunting and requires at some point to commit to one or a few distinctive approaches. However, most articles coincide in that the most effective course design integrates multidimensional goals –cognitive, affective and behavioral—, combines culture-general and culture-specific content, and uses both intellectual and experiential learning processes.

Cognitive, affective and behavioral components

The cognitive component is developed through lectures, readings, class discussions, critical incidents, and small group interactions. It is tested through traditional research papers, for example comparing and contrasting intercultural and cross-cultural interactions between two or more cultures, individual and group presentations and structured exercises. The Affective component is developed through structured exercises, role-play, simulations and exercises involving interaction logs or identity-construction cards. The skill or experienced-based component is developed through simulations, observations, experience-based contacts and case studies.

Textbook selection

Classes are structured from a textbook or a reader, either off-the shelve or made ad hoc by the professor for the course. Most widely used textbooks in introductory courses are:

- Samovar, Porter & McDaniel. Communication between cultures. Wadsworth Publishing Company, 8th. ed. 2012.

- Samovar, Porter & McDaniel, eds. Intercultural communication: A reader. Cengage Learning. and Martin, 14th ed. 2014.

- Martin, J. and T. Nakayama. Intercultural communication in contexts. (2004).

- Martin, J. and T. Nakayama, eds. Experiencing intercultural communication. McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 5th ed. 2013.

Some of these textbooks were originally published in the 1980s and have been tweaked and updated ever since to reflect the change of times. Most of their theoretical approach has aged well, although they have been criticized for focusing on cognitive aspects with too little or nothing on affective and behavioral, and for having a too phalocentric WASP and Eurocentric perspective stressing culture-specific content and communication between national cultures as opposed to interpresonal and intercultural communication within national borders or in multicultural environments. Some of these criticisms have been addressed in the later editions, and it is important to note that these textbooks printed in the 1980s, have been successful in sufficiently keeping up with time, while others have not. The last one of the list, Experiencing intercultural communication is different first because it was first published in 1994, and also because it focuses on a more pragmatic and behavioral approach. The first one, Communication Between Cultures includes chapters on the importance of history and religion which no other textbook I have seen addresses.

I am leaving out some interesting textbooks of course, such as Ting-Toomey Communicating Across Cultures (1999) for example, only becasue they have not been updated or do not have all the supporting materials of the ones I have mentioned earlier.

The introductory course on Intercultural Communication is usually targeted at junior or senior college students. Advanced undergraduates and master students would benefit from the more structured textbook-based approach as it contributes to the clarity of the goals, methods and contents, but would require additional reading materials. A number of other readers and handbooks cover other aspects that may complement those textbooks. For example:

- Holliday, Hyde & Kullman Intercultural Communication: an advanced resource book for students 2nd. Ed. (2010) provides a more schematic approach emphasizing non-specific cultural approach, and both affective and behavioral exercises based on a simple model of identity-otherness-representation and the deconstruction of short fragments of text.

- Piller Intercultural Communication: A critical introduction (2011) Edinburgh UP on another hand focuses on multicultural individuals who may have a variety of cultural affiliations and proficiently interact in a diverse and multicultural environment. It is a comprehensive critical introduction to the field from a discourse analysis, social and anthropological linguistic perspective and illuminates differential prestige of languages and language varieties.

- Ting-Toomey and Oetzel, Managing intercultural conflict effectively (2001) is well grounded in the concepts and theories of both conflict management and intercultural communication, and is unique in the author’s use of system theory.

- Darla Deardorff’s Handbook of Intercultural Competence (2009) seeks to answer the question of «What is intercultural competence.» Her book is intended to be used in advanced Intercultural Communication courses.

Since no single book addresses the specific needs of an introductory intercultural communication class at a professional master’s level a good combination might be:

- Samovar, Porter & McDaniel. Communication between cultures. Wadsworth Publishing Company, 8th. ed. 2012. ($29-$123) ISBN-10: 111134910X | ISBN-13: 978-1111349103)

- Samovar, Porter & McDaniel, eds. Intercultural communication: A reader. Cengage Learning. and Martin, 14th ed. 2014. ($89 ISBN-10: 1285077393 | ISBN-13: 978-1285077390)

- Holliday, Hyde & Kullman Intercultural Communication: an advanced resource book for students 2nd. ed. (2010) ($47, ISBN-10: 0415489423 | ISBN-13: 978-0415489423)

- Plus complementary texts supplied by the instructor both from the other books mentioned, as well as key texts to cover intercultural mass-media communication, framing, intercultural conflict management and resolution and intercultural communication strategizing.